Last year, I wrote a long history of Johnson County video stores that focused mainly on Overland Park’s Hollywood at Home. There was another store that I mentioned in the post, but didn’t dive deep on because 1) the post was already large enough, and 2) I was hoping to get some pictures of the store and give it its own post. Well, my deadline has passed, and unfortunately my quest for quality pictures continues. However, I do have a tale to tell, friends. So gather ‘round and hear all about the life and times of Lenexa’s majestic Video Library – once the largest video store in all of Johnson County, and probably even the entire Kansas City metropolitan area.

It all began in the early-to-mid 1980s. Holly DeNeff was in dental school, but had come to feel that dentistry wasn’t the right fit for her after all. She wanted to start her own business, and started looking around for the right industry. At the time, there were two boom industries for budding entrepreneurs: tanning salons and video stores. Holly mulled both of them over, working briefly at both to learn the businesses from the ground up. She worked her way up to a store manager position at a National Video (a national chain with several locations in the area) and thought that maybe she’d found her industry.

She went to her parents, David and Jean DeNeff, and pitched a business plan to them. David was working for Hudson Oil at the time, but he had some background in retail. Jean was a bookkeeper. They were excited about the idea of starting a video store, and together they all founded Video Library.

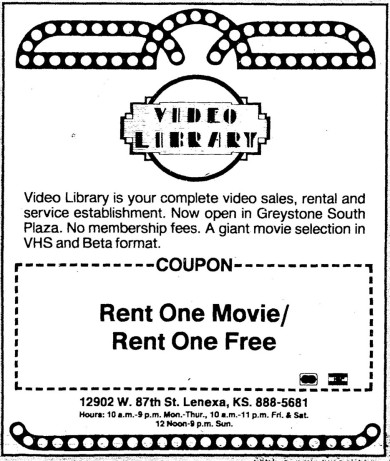

The store moved twice in its lifetime, although never very far. The very first location was 12902 W 87th Street, a roughly 1,400 square-foot space two doors east of Tanner’s near the 87th and Pflumm intersection in Lenexa, KS. It opened on April 16, 1985. Jean told me that she hired a man who had put in a patio at their house to install shelves and the counter and everything at the store. “And it worked out!” she laughed. “He did a good job!”

Jean said that they had maybe two other employees when they first opened, but otherwise it was just her, Holly, and David – who mostly would come in to work on his weekends because he enjoyed it so much. (David and Jean’s son Chris was too young to officially work at the store at the time, but eventually he would come to work at and then own Video Library.)

They had the store set up so that the cases for the movies were out on display on the shelves, and the customer would bring the case to the counter. The tapes were all held behind the counter, and whoever was working would mark down the rental by hand on a data sheet. The store didn’t have a computer yet, so the video inventory was kept in a physical spreadsheet. When people set up rental accounts, they would fill out the membership form with driver’s license and credit card information, and then be good to go.

Jean said that the first title they ever rented out was “The Karate Kid,” and that the guy who rented it from them wound up working for the store years later.

Initially Video Library also sold VCRs, but they gave up on that quickly because they found that customers tended to purchase those at larger electronics stores. After they stopped selling them, they rented VCRs out to people who wanted to rent tapes but didn’t yet have the machines to play them. “I remember getting one back that had tire marks right across the top of it,” Jean told me, laughing. “He told me he rented like that! And I’m like, ‘I don’t think so!’”

She also told me about a time when a woman called the store saying that a tape she’d rented had become trapped in her VCR. She’d tried everything, but couldn’t get it out. After they closed, Jean and Holly actually went over to the woman’s house to see if they could help her remove it. As it turned out, the woman was very new to VCR technology and had failed to do one key thing: Plug the machine in.

Jean told me that business was pretty good from the start… with one exception. “At one point, the Royals were winning everything, and I think that weekend that they won the pennant, we hardly did any business.” She laughed. “And it was really scary!” Nevertheless, business quickly rebounded and the DeNeffs were motivated to grow their store even more. They added more movies to their collection and started renting video games.

By 1988, Video Library had outgrown its first home, so it moved into an approximately 7,000 square-foot space at the west end of the same strip mall. For the new location, the DeNeffs hired a decorator and changed the color scheme of things. They got black shelves so that the VHS cases would pop a little more, and they switched everything over to computers so the business ran much more smoothly. Well… with one exception.

“I remember one Saturday,” Jean told me. “My husband called me and said, ‘I just deleted the entire inventory of the store.’” She laughed, remembering the panic they all felt at the time. Through some accident, David had managed to delete everything. However, they were quickly able to track down the guy they’d purchased the computer system from (who was in Detroit), and he helped them put everything back together with minimal data loss.

While they were at the second location, David retired from Hudson Oil (where he was then Vice President) and started working solely at the video store. It sounded like Chris began working at the store full-time as well. Holly, on the other hand, jumped ship. She married one of the video distributors they’d met through the store and moved down to Florida. Personally, I don’t know if I would have left a job at a video store for true love, but some people have different priorities, I guess.

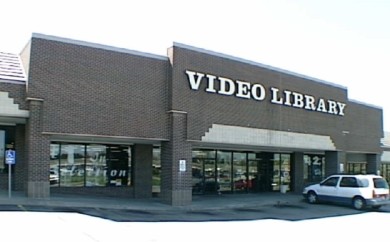

Then came the big one: In October 1990, Video Library hopped across the street and landed in its final home: 12831 W 87th St. It was a massive three-level, 10,000 square-foot space, and they signed a ten-year lease for it. Jean said that business really picked up after the move.

I asked Chris about the layout of the store, and he said that in the back room, they had an office where Jean handled all the accounting and bookkeeping. David was responsible for the purchasing and day-to-day operations. And there was a separate place in the back where they had a work bench where staff spent many hours doing all the preparation work for the inventory. The rest of the employees were out front on the floor or behind the counter.

Their inventory was so large by the time they got to the third location that they started putting the tapes out on the shelves with the cases. There were simply too many movies and games to keep them behind the counter anymore.

Also, I wasn’t sure if this was new to the third location, or something they had done in the earlier spots, but Chris and Jean both told me that one thing they did to set their store apart was have their employees wear uniforms, which were khakis and a pink shirt. (Hey, it was the ‘90s!) They wanted to stand out from other mom-and-pop shops by having everything look as professional as possible. Jean even hired a woman to come in every week and dust the shelves to keep things nice and sparkly.

In the new storefront, they added LaserDiscs to their rental options and even briefly experimented with selling music. Chris ran a music store on the bottom level called “Pepper’s” for a while before transitioning that section of the store over to video games. He built onto the store’s already-sizable inventory of video games and curated a massive collection of games, some of which were imported and very hard (if not impossible) to find anywhere else. The gaming section truly set the store apart from other area video stores, and Video Library regularly hosted video game contests. Attendees may recall the large Mario statue that used to live in that section of the store, which Chris still owns.

Jean remembered one time when they needed to clear out some of the video game inventory. David put an ad out saying that they were going to be selling off old video games starting on a specific day. She said that morning, there was a line outside the door and when they opened, mothers scrambled in and grabbed the games faster than David could put them out on the sale table. “He was afraid for his life!” she said with a chuckle.

Video Library did some print advertising and gave out coupons and had a “reward bucks” kind of program where people could earn free rentals. On the weekends, they often brought in a clown to give out balloons or had a woman on roller skates going around giving candy to the kids. Business was very good in the 1990s, but with competitors popping up all over they wanted to remain competitive.

Jean said that as business got rolling, they could easily do $10,000 in $3 rentals over the course of a weekend. Their busiest days were always Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve, and the only day of the year they were closed was Christmas day. Although even on Christmas, somebody had to stop by the store a few times and empty out the night drop bin, because so many items were getting returned that it kept filling up. She also mentioned that whenever a big snowstorm was predicted, videos would start flying off the shelves.

The Lenexa Police Department was right down the street. In fact, police and firefighters could rent one movie and get another free. But despite the proximity of the police department, the store was robbed on occasion. Jean said she remembered one time where somebody broke out a window near the adult video section after hours. They stole a row of movies, but left blood all over the place, getting at least some cosmic justice.

Another time, somebody went into the bathroom before the store was closed and climbed up into the ceiling. Before they left, employees noticed that some debris had fallen from the ceiling, assumed it was rodents, and made a note to have somebody out to take care of it in the morning. “But it was somebody waiting to rob the store,” she told me. “And he jumped down [after everybody was gone], and we had a big alarm system in there, so I think he ran out the back real quick.”

When I asked them what titles they remember doing big business, both said the same thing right away: “Titanic.” When it finally came out to rent, David pulled the slatwall panels that held the video racks out at an angle to make it look like the hull of a ship.

After 15 years, David and Jean decided to retire from the video store and sold the shop to Chris and his then-wife Carol in 2000. Business was still booming then, and Chris said that in the store’s peak years (around 1998 to the early-to-mid-2000s) he remembered doing something like $30,000 per week. He said that they had as many as 40 employees at one point, which obviously offset profits, not to mention the $20,000 monthly rent.

Chris told me that over the years, they had a lot of competition from nearby Blockbuster, Hollywood Video, and Flicks and Discs shops, but that Video Library was always the big dog on the block. The main thing that set them apart was their massive selection. A 1998 advertisement in the Kansas City Star reads, “Video Library: 42,000 Videos In Stock!” By the time they closed in 2007, the selection had swelled to 60,000. And to clarify, I believe that is individual titles, meaning if they had four copies of “Ghostbusters” on VHS, that still counted as only one title. For comparison, your average Blockbuster back in the golden days of video stores was unlikely to even have 10,000 titles. That may seem unbelievable, but the store truly was massive. I’ve been to a lot of video stores in my day, and the only one I’ve been inside that compared to Video Library was Movie Madness in Portland, Oregon, which is now (at 80,000 titles) a nationally recognized treasure. Part of how Video Library amassed such a huge collection was that they held onto their VHS tapes when a lot of other stores fully transitioned over to DVD in the late ‘90s. A ton of movies came out on VHS that were never released on DVD (or Blu-ray, or 4k Blu-ray, etc.), so hanging onto those tapes when other stores deemed them obsolete made Video Library the place to go for movie buffs searching for a title they couldn’t find anywhere else.

I only managed to visit the store once, as I grew up pretty far away from it, but I still remember the chilly January day in 2006 when I walked in there and found essentially every movie I had ever wanted to see plus tens of thousands of others. I’m a big horror fan, and I rented “Prince of Darkness,” “Silent Scream,” “Twilight Zone: The Movie” (which admittedly was a re-watch), and “Trilogy of Terror.” The latter three were still only available on VHS at that point, and quite difficult to find. It wouldn’t be hard for me to track any of these titles down today in the age of streaming, internet piracy, and “boutique” Blu-rays – not to mention fantastic public library systems like Johnson County Library – but in 2006 I felt like I’d stumbled into the Lost City of Zinj (only without all the killer mutant apes). It was such an incredible treasure trove, just sitting there in the middle of suburbia.

Alas, nothing gold can stay. As technology changed, business faded fast. By the mid-2000s, companies like Redbox (which rented out popular new release DVDs from strategically placed vending machines) and Netflix (which offered discs by mail at the time) had begun slaughtering video stores all around the country. In addition to those woes, the city of Lenexa made some changes to 87th Street that dragged on and on. The 87th Street exit off of I-35 was closed for two years and immediately in front of the store easy access to Video Library’s strip mall was cut off for months.

“Let me put it this way,” Chris said of the declining business. “It was like when you turn on a faucet full blast. You’ve got that nice water flowing. That was the store at its peak. Well, eventually it ended up being like a trickle. It was still coming through, but it was not doing well.”

In January of 2007, Netflix launched their streaming video service, and the writing was on the wall for video stores. Video Library closed to do an inventory over Memorial Day weekend that year, and when they re-opened, they announced that the store was closing and that everything on the shelves was for sale. They hired a company to handle the liquidation, and although Jean was sick at the time and unable to help, David came up from Florida to help Chris and Carol close the store down.

The store officially closed on July 31st, 2007.

In my interviews with them, both Chris and Jean repeatedly mentioned how fun the job was and how much they loved the vast majority of their customers. Both said they’d befriended many of their customers, and were still in contact with some of them. Jean said that a big perk of the job was that the customers were almost always happy because they were doing something they enjoyed on their time off. Although, “once in a while you’d get somebody that was a really sick” and just needed a stack of tapes to help carry them through their flu. She spoke fondly of their regular customers and said that she got to watch a lot of kids grow up. “It was nice!”

After they sold the store in 2000, David and Jean bought a motorhome and traveled for months at a time. Eventually they sold their Kansas home, traveled all over Canada and the United States (hitting every state except for Hawaii and Alaska), and then settled in Florida. Chris also moved to Florida after closing the store, and Holly is still down there as well. David passed away in 2019.

Although it wasn’t a place I got to visit more than once, Video Library still ranks as one of the coolest places I’ve ever been. It was a true shrine for movie lovers, and a jewel of Johnson County while it lasted. Stay tuned, because I still hope to get some pictures of it to share in an update on this blog some day. Trips to Video Library were a weekend ritual for hundreds of people in Lenexa and the surrounding cities, so somebody out there has got to have something.

At the end of our conversation, Chris sighed. “You’ll never find another video store like Video Library in the rest of your life, I can tell you that.” He gave a wistful laugh. “The reason for that is because of the people who owned it and the people who ran it.”

So here’s to you, Video Library! The biggest video store Johnson County ever knew.

Thanks for reading, and thanks very much to Chris, Jean, and Holly DeNeff for their participation in this blog post. If any readers have memories of the store they’d like to share (or pictures!) please leave them in the comments and/or email me at kellerm@jocolibrary.org.

-Mike Keller, Johnson County Library