By the turn of the 20th century, industrialization in Kansas City resulted in overcrowding, pollution, and disease. Looking to escape these less-than-desirable conditions, Kansas City’s upper-middle classes sought homes in new suburban developments in northeast Johnson County. The advent of the electric trolley led to “streetcar suburbs,” which made transit into downtown accessible and convenient.

One such suburban neighborhood was planned by Richard Weaver (R.W.) Hocker, who was a banker and real estate developer in Kansas City, Missouri. Envisioning early suburban development in Johnson County, the “R. W. Hocker Subdivision” was platted in 1910 for eight 5-acre lots. One of two houses originally built, the “Walker House,” was added to both the State and National Registers of Historic Places in March 2017.

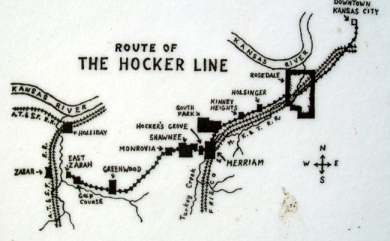

This image from Google Maps shows the Walker House as it appears today at 5532 Knox Street.

The Walker House is a single-family dwelling built between 1906 and 1911 (the Kansas State Historical Society estimated 1910). The home, located at 5532 Knox Street, was built as a “spec house,” short for “speculative,” essentially serving as a model for the neighborhood’s intended development. The home’s first occupant was Mrs. Azubah Denham, the wife of Rev. B.Q. Denham. Rev. Denham was a popular pastor in Johnson and Wyandotte Counties in the 1890s. Between 1904 and 1910, however, he had become infamous for adultery and indecency scandals in Buffalo and New York City. In 1911, Azubah Denham purchased the Walker House in her name only for $5,500 ($137,500 in 2015). In 1920, many working class families lived on less than $1,500 per year, so the home’s price illustrates the intended middle-class nature of Hocker Subdivision.

Architecturally, the Walker House is indicative of the Kansas City Shirtwaist Style, named for ladies fashion at the beginning of the 20th century. Shirtwaist dresses included a seam at the waist where the material often changed. The Shirtwaist influence is evident in the Walker House: a single-floor local limestone exterior, an upper floor and a half of cedar clapboard, and flared gable eaves on the eastern face and one-story porch. Inside, original woodwork, including oak and pine hardwood floors, contribute to the historic character. The Walker House originally sat on a large 5-acre lot, but today occupies just .31-acres.

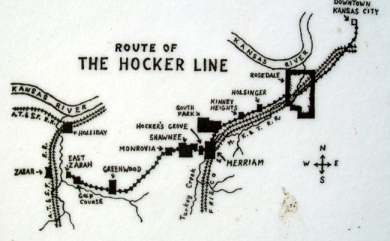

Hocker also platted “Hocker’s Grove” in 1915. This neighborhood contained 1-acre lots for modest—but still middle-class—Craftsman bungalow homes. Just seventeen were originally constructed. Both neighborhoods were within a half-mile walk from the “Hocker Line,” an inter-urban, electric trolley that was speculated to extend from Kansas City to Lawrence and even Topeka (it reached as far as Mill Creek, to the east of Zarah, or about two miles west of I-435 today). By 1907, the trolley ran the the seven-and-a-half miles between Kansas City and Merriam. Residents could reach Union Station in 35-minutes, the intersection of 12th and Main Streets in 45-minutes, and make connections to Kansas City’s urban trolley line along Southwest Blvd.

Hocker promoted his neighborhoods with the slogan, “The Home For You.” A promotional booklet printed in 1915 testified that buyers would find “an ideal home in an ideal location with ideal surroundings.” The booklet indicated that the “modest, artistic homes in a restricted neighborhood” were equipped with natural gas, fronted on macadamized rock roads, and were located in “natural and picturesque beauty.” Buyers could take advantage of flexible deferred payment plans, as well. The “restricted neighborhood” wording communicated to white, middle-class buyers that the area was reserved as residential for a twenty-five year span, and that no African Americans could purchase or lease the homes there for 100 years. This developer’s tool of racial segregation, often referred to as a “deed restriction,” was used throughout Kansas City and Johnson County’s suburban neighborhood developments, as well as across the nation during the 20th century suburban boom.

An undated map of the route of the Hocker Line electric trolley. The trolley line followed the Frisco and Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad lines. (Johnson County Museum)

Both of Hocker’s neighborhood developments were located near Hocker Grove Park, a 40-acre amusement park that Hocker planned and built with O.M. Blankenship between 1907 and 1908. The park was located on Hocker Drive, north of Johnson Drive today. This amusement park featured roller-skating, dancing under a large pavilion with a Wurlitzer automatic band organ (the pavilion doubled as a basketball gym), and was the site of balloon ascensions, professional boxing matches, and picnics. Families rode the Hocker Line from Kansas City to enjoy picnics in the natural setting. There was also a 2,000-seat grandstand for watching baseball games, an extremely popular sport at the time. A “Trolley League” soon developed with six semi-professional baseball teams.

The Hocker Grove “Trolley League” baseball team, c. 1908. (Johnson County Museum, 1990.025.018)

Hocker was not the only real estate entrepreneur working in the area. Increased real estate competition in and around Merriam at the time of Hocker’s developments may have limited the construction there. After all, despite the beauty and convenience of Hocker’s two neighborhoods, only 19 homes were built between them. William B. Strang’s competing interurban trolley line and his suburban developments, most notably Overland Park, were located nearby and were equally convenient, beautiful, and middle-class in nature. Hocker died in 1918, and his amusement park closed the following year. After more than a decade of financial difficulty, the Hocker Line trolley closed for good in 1934. By then the automobile had become accessible for Johnson County families.

In the century since the construction of the Walker House in the R. W. Hocker Subdivision and the smaller Craftsman homes in Hocker’s Grove, most of the empty lots have been built upon, the large lots have been subdivided, and many historic homes have been remodeled or razed. Yet it is still possible to discern the beauty of the location and, with Interstate 35 following the Hocker Line into Kansas City almost exactly, the convenience remains evident. Hocker’s suburban dreams for his neighborhoods nestled between Merriam and Shawnee have been thoroughly realized today, if not during his lifetime.